The epithelial tissue in the human body serves crucial protective and functional roles, differing significantly across various organs. Particularly, the epithelium of the esophagus and stomach embody unique characteristics tailored to their specific functions in the digestive system. While both tissues serve as linings, their structural and functional disparities are profound and consequential for both health and disease.

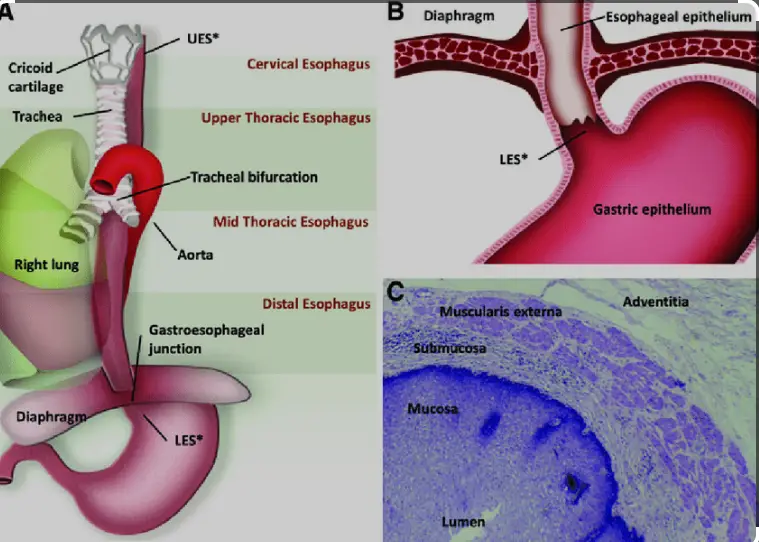

The esophageal epithelium is a stratified squamous type, designed to withstand the wear and tear of solid foods passing through, whereas the gastric epithelium is a simple columnar type that secretes enzymes and acid for digestion. These fundamental differences impact their disease profiles, susceptibility, and treatments, setting a distinct clinical importance for each.

Diving deeper into the specifics, the esophageal epithelium protects against mechanical damage while the gastric epithelium must also manage chemical challenges from gastric acid. Each type of epithelium not only reflects the demands of its environment but also its vulnerability to specific pathologies, including various forms of cancer and inflammatory conditions.

Esophageal Epithelium

Structure Details

The esophageal epithelium is a specialized tissue that lines the interior of the esophagus. Unlike many other epithelial tissues, it is composed of stratified squamous cells, which are arranged in layers. This structural arrangement is critical because it provides a tough barrier against the mechanical stress of swallowing food. The cells closest to the surface are flat and scale-like, designed to withstand friction and shear forces as food moves from the mouth to the stomach.

The basal layer of the esophageal epithelium contains stem cells that continually divide to replace the superficial cells that are shed during the digestive process. These new cells gradually move towards the surface as they mature, a journey that takes approximately two to three weeks. The entire lining lacks hair follicles, sweat glands, or sebaceous glands, which distinguishes it from skin, despite their similar appearance under a microscope.

Function Overview

The primary function of the esophageal epithelium is protection. It shields the underlying tissues from mechanical damage (such as abrasions from rough food particles), chemical harm (from acidic or spicy foods), and pathogenic invasion. Furthermore, its smooth, lubricated surface aids in the efficient conveyance of food to the stomach, facilitating a seamless digestive process.

- Protects underlying muscles and nerves

- Facilitates the smooth passage of food

- Prevents backflow damage from stomach acids

Common Issues

The esophageal epithelium can be susceptible to several problems, most notably:

- Acid Reflux: Frequent exposure to stomach acid can damage the epithelial cells, leading to gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD). Symptoms include heartburn, chest pain, and difficulty swallowing.

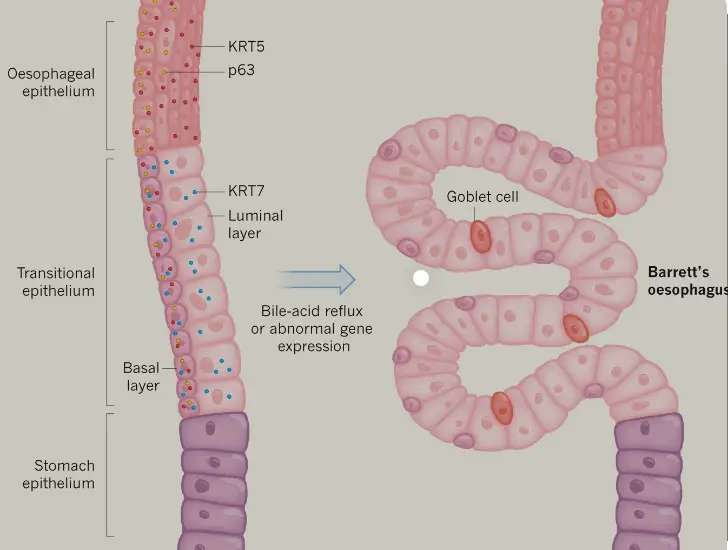

- Barrett’s Esophagus: In response to chronic acid exposure, the squamous cells can transform into columnar cells, a condition known as Barrett’s Esophagus, which significantly increases the risk of esophageal cancer.

- Esophagitis: Inflammation of the esophagus, often caused by infections, allergies, or acid reflux, can lead to discomfort and swallowing difficulties.

Gastric Epithelium

Structure Description

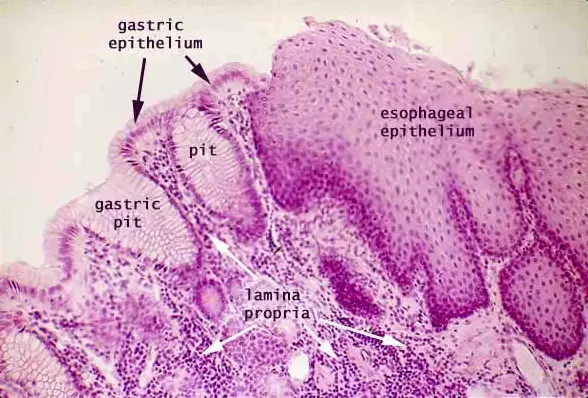

The gastric epithelium lines the stomach and is vastly different from its esophageal counterpart. It is made up of simple columnar epithelium and is heavily specialized to handle the acidic environment of the stomach. This lining includes mucous cells, which produce a bicarbonate-rich mucus that coats the stomach walls, protecting them from digestive acids and enzymes.

The gastric pits, tiny indentations in the gastric mucosa, lead into gastric glands that secrete gastric juice. This juice is a mixture of hydrochloric acid, digestive enzymes, and mucus. The unique cellular composition and continual secretion not only aid digestion but also serve as a first defense line against ingested pathogens.

Primary Functions

The primary functions of the gastric epithelium include:

- Secretion of Gastric Juices: Enzymes and acids crucial for food digestion are produced by specialized cells within the gastric glands.

- Barrier Protection: The mucous layer produced by the epithelial cells protects the stomach lining from self-digestion by the highly acidic gastric juice.

- Absorption of Selected Substances: While most absorption takes place in the intestines, the stomach epithelium absorbs some substances like water, alcohol, and certain medications.

Typical Problems

The gastric epithelium can encounter several issues, notably:

- Gastritis: This inflammation of the stomach lining can be caused by excessive alcohol consumption, chronic stress, certain medications, or bacterial infections.

- Peptic Ulcers: These are sores that develop on the stomach lining when the protective mucus is diminished, allowing digestive acids to erode the epithelium.

- Stomach Cancer: Abnormal growth of stomach cells, often related to chronic gastritis or Helicobacter pylori infection, can lead to cancerous formations in the gastric epithelium.

Key Differences

Cellular Structure Comparison

The cellular structures of the esophageal and gastric epithelium are distinctly different, tailored to their specific roles within the digestive system. The esophageal epithelium is comprised of stratified squamous cells, which are multiple layers of flat cells providing a robust barrier against physical damage. In contrast, the gastric epithelium features simple columnar cells, which are single-layered cells that facilitate secretion and absorption.

- Esophageal epithelium: Multi-layered, non-keratinized for flexibility and moisture retention.

- Gastric epithelium: Single-layered, specialized with mucous cells and gastric pits for enzyme and acid secretion.

Functional Distinctions

Functionally, these tissues reflect their structural adaptations. The esophageal epithelium’s primary role is protective, guarding against mechanical damage from swallowed food. The gastric epithelium, however, is primarily involved in digestion, secreting acids and enzymes necessary for breaking down food.

- Protection vs. Digestion: The esophagus protects against damage, while the stomach breaks down contents.

- Secretion: Only the gastric epithelium secretes digestive juices, critical for nutrient breakdown.

Disease Susceptibility Contrast

Disease susceptibility in these tissues also highlights their differences. The esophageal epithelium is prone to disorders like Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal cancer, primarily from chronic exposure to acid reflux. Gastric epithelium, however, is more susceptible to conditions like gastritis and stomach ulcers, largely due to bacterial infections and the harsh acidic environment.

- Acid reflux impacts the esophagus, potentially leading to cellular changes and cancer.

- Helicobacter pylori infection in the stomach can cause ulcers and increase cancer risk.

Clinical Significance

Diagnostic Implications

The distinctive features of these epithelia have important diagnostic implications. For instance, a biopsy of the esophagus might show signs of squamous cell carcinoma, whereas a biopsy from the stomach might reveal adenocarcinoma or signs of Helicobacter pylori infection.

- Biopsy techniques vary: Brush biopsies are often used in the esophagus, while deeper biopsies are used in the stomach to assess glandular structures.

- Endoscopic evaluation: Differentiating features in endoscopy can help localize lesions and guide biopsies.

Treatment Considerations

Treatment strategies also differ significantly between esophageal and gastric issues. Antacids and acid blockers like proton pump inhibitors are common in treating esophageal problems, while antibiotics are essential in treating Helicobacter pylori infections in the stomach.

- Esophageal treatments often focus on controlling acid and healing inflamed tissues.

- Gastric treatments may include eradication of infection and protection of the mucosal lining.

Future Research Directions

Future research is vital in enhancing understanding and treatment of conditions affecting these epithelia. Areas of interest include:

- Genetic markers: Identifying genetic factors that contribute to disease susceptibility and progression.

- Barrier enhancements: Developing new treatments that can enhance the protective barriers of these epithelia.

- Microbiome studies: Exploring the role of the microbiome in diseases of the esophagus and stomach, particularly how it influences inflammation and cancer risks.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is epithelial tissue?

Epithelial tissue is a protective bodily tissue that lines both the internal and external surfaces, including organs and blood vessels. It serves as a barrier against microorganisms, regulates exchange of substances, and provides sensory surfaces and secretory functions.

How does esophageal epithelium differ from skin?

Esophageal epithelium is similar to skin as both are stratified squamous types; however, the esophageal lining is non-keratinized, allowing it to stay moist and better handle food passage, unlike the keratinized, dry skin designed for external protection.

Why is gastric epithelium prone to ulcers?

Gastric epithelium is exposed to harsh conditions due to stomach acids and digestive enzymes. It’s prone to ulcers when protective mechanisms fail, often due to infections, excessive acid production, or chronic use of certain medications like NSAIDs.

How do diseases affect esophageal and gastric epithelium differently?

Diseases such as GERD primarily affect the esophagus, leading to inflammation and damage from stomach acid backflow, while conditions like gastritis directly impact the gastric epithelium, causing inflammation due to infections or chemical irritants.

Conclusion

The epithelial tissues of the esophagus and stomach are fundamental to our understanding of digestive health and disease. Their differences, while minute at a microscopic level, have vast implications for clinical practices and patient outcomes. Recognizing these distinctions not only aids in accurate diagnosis but also in tailoring specific treatment strategies for diseases affecting each area.

In conclusion, the careful study of esophageal and gastric epithelium enhances our capabilities in managing and treating a range of gastrointestinal disorders. It underscores the importance of specialized medical knowledge and patient-specific therapeutic approaches in gastroenterology.