Campylobacter and Helicobacter are two genera of bacteria that, while similar in name and certain biological features, present distinct challenges in the realm of medical diagnosis and treatment. Both are primarily known for their role in human gastrointestinal disorders, but their differences are crucial for effective medical response. As pathogenic bacteria, they have a significant impact on public health worldwide, making their accurate identification and understanding essential.

Campylobacter is typically associated with foodborne illnesses and is often found in undercooked poultry, while Helicobacter, particularly H. pylori, is notorious for its role in chronic conditions like gastritis and ulcers. These bacteria differ not only in the health conditions they provoke but also in their environmental habitats, modes of transmission, and the mechanisms by which they cause disease.

Despite their similar-sounding names, Campylobacter and Helicobacter affect the body in different ways, necessitating unique approaches to diagnosis and treatment. For those in medical and health fields, as well as patients managing infections, distinguishing between these two can be the key to effective treatment and management.

Bacteria Basics

Campylobacter Overview

Habitat and Transmission

Campylobacter species are primarily found in the intestines of birds and mammals. They are widespread in poultry, making undercooked chicken a common source of infection. Other sources include unpasteurized milk and contaminated water. Campylobacter thrives in these environments due to its ability to colonize a wide range of animal hosts, which serve as natural reservoirs.

Transmission to humans typically occurs through:

- Consuming contaminated food (especially poultry).

- Drinking contaminated water.

- Contact with infected animals.

This bacteria can also spread from person to person through poor hygiene practices, although this is less common.

Common Symptoms

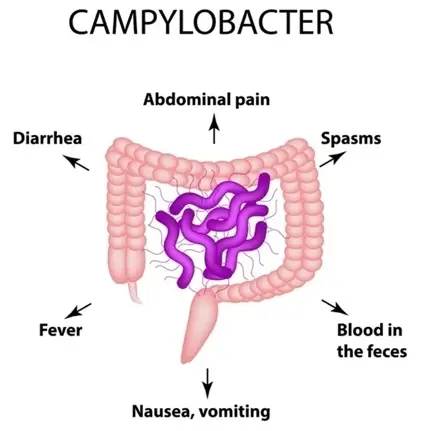

Infection with Campylobacter typically leads to gastrointestinal illness known as campylobacteriosis. Symptoms often include:

- Diarrhea (often bloody)

- Abdominal pain

- Fever

- Nausea and vomiting

Symptoms usually appear within two to five days after exposure and can last about a week. In some cases, especially in children and immunocompromised individuals, the infection can be more severe and may lead to complications.

Helicobacter Overview

Unique Characteristics

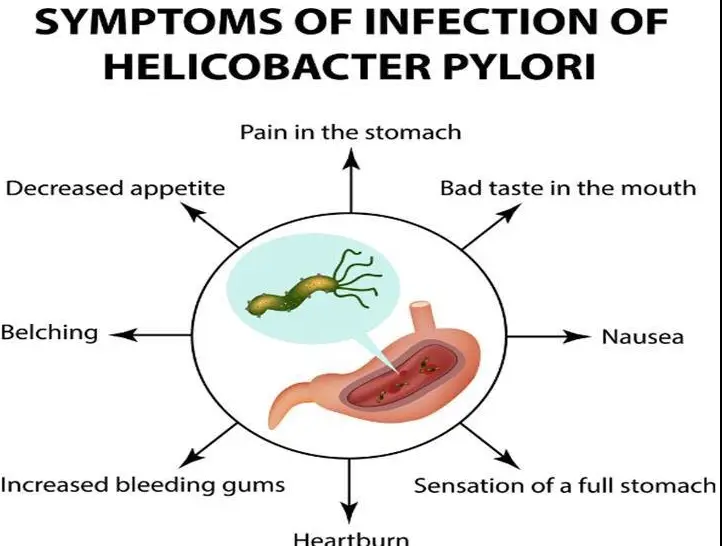

Helicobacter pylori is adapted to live in the harsh, acidic environment of the stomach. Its unique characteristics include:

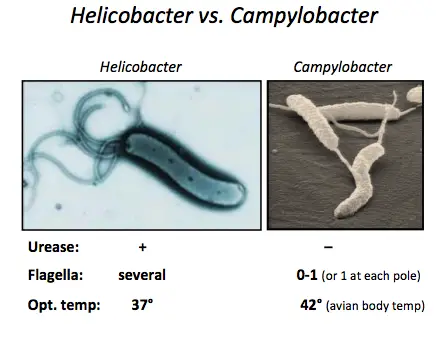

- Shape: The bacterium’s spiral shape helps it penetrate the stomach’s mucous lining.

- Urease production: This enzyme neutralizes stomach acid, creating a more hospitable environment for the bacterium.

These traits allow H. pylori to persist in the stomach for years, often without causing immediate symptoms.

Health Implications

Helicobacter pylori infection is primarily linked to several significant gastrointestinal diseases:

- Peptic ulcers: Open sores that develop on the inner lining of the stomach and the upper part of the small intestine.

- Gastritis: Inflammation of the stomach lining, which can be chronic.

- Stomach cancer: Particularly non-cardia gastric cancer and mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma.

The presence of H. pylori is a strong risk factor for these conditions and makes its detection and treatment crucial for affected individuals.

Key Differences

Physical Traits

Cellular Structure

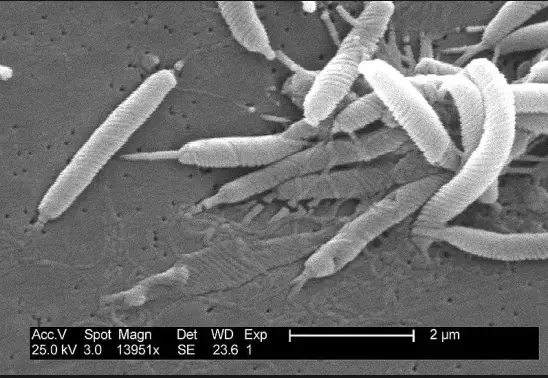

Campylobacter bacteria are slender, spiral-shaped, and motile with flagella at one or both ends of the cell, aiding in their mobility. In contrast, Helicobacter pylori is also spiral-shaped but generally more tightly coiled and equipped with multiple flagella, which make it highly motile in the viscous environment of the stomach mucosa.

Growth Conditions

Campylobacter prefers a microaerophilic environment, thriving best in reduced oxygen levels, whereas Helicobacter pylori requires an even more specific set of conditions due to the acidic nature of its habitat, the human stomach. This environment demands adaptations not required for most other bacteria.

Health Effects

Diseases Caused

While both bacteria cause gastrointestinal distress, their associated diseases differ markedly in severity and chronicity. Campylobacter is often associated with acute gastrointestinal symptoms and rarely leads to more severe outcomes. On the other hand, Helicobacter pylori is implicated in chronic diseases that can lead to significant long-term health issues.

Severity and Duration

The effects of Campylobacter infection are typically acute, with symptoms resolving within a week, though occasional complications like reactive arthritis can occur. Helicobacter pylori, however, causes chronic infections, which if left untreated, can lead to life-threatening diseases such as stomach cancer.

Diagnosis Techniques

Identifying Campylobacter

Laboratory Tests

To diagnose Campylobacter infections, laboratories perform tests such as:

- Stool cultures: The primary method for detecting presence.

- PCR tests: For rapid identification of bacterial DNA.

Diagnostic Challenges

The diagnosis can be hindered by the bacteria’s delicate nature, requiring specific conditions for transportation and culture.

Identifying Helicobacter

Testing Methods

Helicobacter pylori is typically detected using:

- Breath tests: Non-invasive and widely used.

- Stool antigen tests: Effective for confirming eradication post-treatment.

- Endoscopic biopsy: For direct observation and culture.

Treatment Implications

Understanding the nature of the infection influences treatment decisions significantly. Standard treatments include antibiotics and drugs to reduce stomach acid. Early diagnosis can prevent the progression of severe gastrointestinal diseases associated with H. pylori.

Treatment Strategies

Treating Campylobacter

Recommended Medications

For most healthy adults, Campylobacter infections are self-limiting and may not require specific antibiotic treatment. However, in severe or prolonged cases, especially in vulnerable populations such as children and the immunocompromised, the following medications may be prescribed:

- Azithromycin: Effective in reducing the duration of symptoms.

- Erythromycin: Another effective choice, especially for children.

- Fluoroquinolones: Used in some cases, but resistance is increasing.

It is essential to take antibiotics only when prescribed by a healthcare professional to minimize the risk of developing antibiotic resistance.

Lifestyle Adjustments

Alongside medical treatment, certain lifestyle adjustments can help manage symptoms and prevent the spread of infection:

- Stay hydrated: Drink plenty of fluids to prevent dehydration due to diarrhea.

- Practice good hygiene: Wash hands thoroughly after using the bathroom or handling food.

- Isolate if necessary: To prevent spreading the infection to others, especially in household settings.

Treating Helicobacter

Long-term Management

Managing Helicobacter pylori infection requires a coordinated approach often involving a combination of antibiotics and acid-suppressing medications. The typical regimen includes:

- Dual therapy: A proton pump inhibitor (PPI) and amoxicillin or a macrolide antibiotic for 14 days.

- Triple therapy: A PPI, clarithromycin, and either amoxicillin or metronidazole, depending on resistance patterns.

Patients must follow the full course of treatment to ensure complete eradication of the bacterium.

Prevention Tips

Preventing H. pylori infection can be challenging due to its mode of transmission. However, the following practices can reduce risk:

- Test and treat: Identifying and treating infections in family members can prevent spread.

- Ensure food safety: Proper cooking and food handling can help prevent infection.

- Maintain personal hygiene: Frequent handwashing, especially before eating and after using the bathroom, is critical.

Epidemiological Data

Campylobacter Statistics

Infection Rates

Campylobacter is one of the most common causes of diarrheal illnesses in the world. Annually, it affects over 1.3 million individuals in the United States alone.

Demographic Variability

Infection rates are highest among children under five years old and young adults aged 15-29. These groups are particularly susceptible due to less developed or compromised immune systems.

Helicobacter Statistics

Global Impact

Helicobacter pylori infects about half of the world’s population, with higher prevalence in developing countries due to overcrowding and lower standards of sanitation.

Risk Factors

Risk factors for H. pylori infection include:

- Living in crowded conditions: Increases the likelihood of person-to-person transmission.

- Lack of clean water: Facilitates spread through contaminated drinking sources.

- Poor sanitation practices: Contributes to the spread through fecal-oral routes.

Current Research

Advances in Campylobacter

Vaccine Development

Research into developing a vaccine for Campylobacter is ongoing. Recent studies have focused on identifying key antigens that can trigger an immune response without causing illness.

Future Prospects

The future of combating Campylobacter includes:

- Enhanced surveillance to monitor and respond to outbreaks swiftly.

- Improved diagnostics that offer quicker and more accurate detection.

Advances in Helicobacter

New Treatments

Recent breakthroughs in treatment for Helicobacter pylori involve the development of more effective drug combinations that reduce the risk of antibiotic resistance.

Ongoing Studies

Ongoing research aims to better understand the mechanism of H. pylori‘s resistance to current treatments and to develop strategies for overcoming this challenge, potentially including novel therapeutic agents or targeted therapies.

FAQs

What is Campylobacter?

Campylobacter is a genus of bacteria known primarily for causing foodborne diseases. It is most commonly contracted from consuming undercooked poultry or foods contaminated with intestinal contents of infected animals. Symptoms typically include diarrhea, fever, and abdominal cramps, and can be severe in young children, the elderly, and immunocompromised individuals.

How does Helicobacter affect the stomach?

Helicobacter, specifically Helicobacter pylori, primarily infects the stomach and upper part of the small intestine. This bacterium causes chronic inflammation (gastritis) and is a leading cause of ulcers in the stomach and duodenum. It is also associated with an increased risk of developing stomach cancer.

Can Campylobacter and Helicobacter be cured?

Yes, infections caused by both Campylobacter and Helicobacter can be treated effectively with antibiotics. However, the choice of treatment may vary based on the specific bacterium, the severity of the infection, and the patient’s overall health. It’s crucial to consult a healthcare provider for a proper diagnosis and treatment plan.

What are the transmission routes for Helicobacter?

Helicobacter pylori is primarily transmitted from person to person via direct contact with saliva, vomit, or fecal matter. It can also be contracted from contaminated water or food. Unlike Campylobacter, which is often associated with poultry, Helicobacter does not typically have a specific food associated with its transmission.

How to prevent Campylobacter infections?

Preventing Campylobacter infections involves proper food handling, cooking, and hygiene practices. It is crucial to cook poultry thoroughly, wash hands and surfaces frequently, and avoid cross-contamination between raw and cooked foods. Drinking pasteurized milk and using clean water can also reduce the risk of infection.

Conclusion

Recognizing the differences between Campylobacter and Helicobacter is crucial for effective clinical management and patient care. These bacteria, while similar in many aspects, necessitate distinct diagnostic and therapeutic approaches due to their different pathological impacts. Understanding these nuances not only aids in the effective treatment but also in the prevention of the spread of these infections.

The ongoing research and development of targeted treatments and preventive measures against these bacteria are vital. By continuing to enhance our understanding and approach to these pathogens, the medical community can better protect public health and improve patient outcomes in gastrointestinal bacterial infections.